by Hazel Ryerson, CAPS | Job Caption/Project Designer

One of the challenges I’ve run into at the KMA Design Studio is how to balance the regulatory accessibility requirements for multifamily housing with the needs of an individual resident. Sometimes it works out that we get to meet a resident before designing their unit renovation, and sometimes we don’t.

Mission Park in Boston is a great example of this challenge. In 2015, Josh Safdie AIA, designed the renovations for the accessible units at Mission Park. This spring we received a call to come back and help them figure out how to make one of the accessible units actually work for the resident who planned to move in. The unit was recently renovated, with a new accessible bathroom, a new accessible kitchen and new 42” pocket doors.

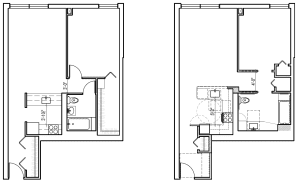

I looked over Josh’s plans before going to Mission Park to meet the future resident, Ms. Levine. In terms of space allocation and minimum dimensions, this unit exceeded the requirements in many places.

The unit on the left is the existing unit pre-renovation. The unit on the right is the renovated unit.

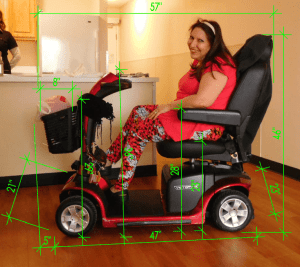

When I met with Ms. Levine on site it became clear that many of the features in the apartment did not work for her, despite meeting the accessibility requirements. First off, Ms. Levine uses a scooter, not a wheelchair. Her scooter has a much larger turning radius than the required 5’ turning radius. This meant that Ms. Levine could not turn around in her kitchen, and making the turn from the hall into either the bedroom or bathroom was extremely difficult. In addition, Ms. Levine primarily uses her left arm, and because of the length of the scooter, she needs to make a side approach rather than a front approach to her appliances.

We came up with four modifications to the apartment to meet Ms. Levine’s specific needs. We rotated the controls for both the kitchen and bathroom sinks so that Ms. Levine could reach them with her left hand. We increased the opening size of the pocket doors by retrofitting the doors to be fully recessed into the pockets so that Ms. Levine would be able to make the turn from the hallway into the bathroom and bedroom. We installed additional grab-bars around the tub and toilet in locations requested by Ms. Levine during a discussion about her daily routines. The updates that we made to Ms. Levine’s unit fell into the category of “reasonable modifications,” and the building management company was more than willing to make the changes.

The truth is, if Ms. Levine moves out, these changes will likely be reversed as it is unlikely that another person with similar needs will be the next person to move in. For me, this renovation of a renovation brought home the point that there really is no single “accessible user” who will move into an accessible unit. To make accessible units work for their actual users, we need to design for modification. We need to make accessible units as flexible and easily modified as possible.